UCG and the Irish Language / Coláiste na hOllscoile, Gaillimh, agus an Ghaeilge

The annual Oireachtas of Gaelic League was held in Galway Town Hall, now the Town Hall Theatre, in 1913. (Courtesy of the Curran family, Dublin)

1. Éamon de Valera (later President), 2. Count George Noble Plunkett, 3. Pádraic Ó Conaire, 4. Seán T. O’Kelly (later President), 5. Seán MacDiarmada, 6. Patrick Pearse, 7. George Russell (AE), 8. Douglas Hyde (later President), 9. Éamonn Ceannt, 10. Constance Markievicz

For a generation of advanced nationalists, the west of Ireland represented the repository of all that was authentically Irish and the Gaelic League and its predecessors sought to restore the Irish language to the forefront of national culture.

In spite of the University’s location on the western seaboard, adjacent to the Irish-speaking Gaeltacht areas, study of the Irish language was marginalised in Queen’s College Galway until the establishment of a permanent chair of Celtic in 1897. The appointment was the result of external pressure as the Queen’s Colleges could no longer ignore the demand for Irish. The Irish Universities Act of 1908 finally established permanent chairs of Irish and from 1913 onwards, the subject became a requirement for matriculation and entry into the National University of Ireland, of which UCG was a constituent College.

Enthusiasm for the Irish language came to be seen as a patriotic duty for nationalists by the turn of the century and by the outbreak of the war, Irish attracted the third largest number of students of any course taught in the College.

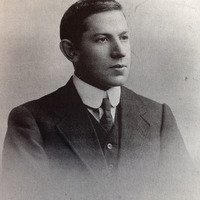

Tomás Ó Máille was appointed the first Professor of the Irish language in the College in 1909. Born to a prosperous farming family in Munterowen, near Maam in Joyce Country, Connemara, he benefitted from a cosmopolitan education in Dublin and Europe. Having studied Old Irish, Breton and Welsh with the pioneering German scholar, Kuno Meyer, he gained his doctorate from the University of Freiburg. Charismatic, broadminded and possessed of a profound intellect, Ó Máille was representative of a generation of educated Catholics who were determined to redress the prejudices of the British state. In his application for Professorship in 1909 he stated his desire, ‘to develop the natural advantages for modern Irish of the situation of the University College in an Irish speaking district so as to make it a great centre of Irish learning and Celtic Studies.’ His appointment was a significant step in securing the place of the Irish language at the forefront of Irish scholarship and establishing its important role in the University.

Prejudice against the language remained, however, and in the aftermath of the 1916 Rebellion, the local unionist newspaper, the Galway Express, attacked the alleged politicisation of the Irish language at the University, explicitly linking the language with support for political violence:

So much for our College! In the country the whole system of education must be revised and supervised. Let the old language of Ireland have every chance, but let it never again be allowed to cover the spread of sedition. Let us try and realise that it is much more useful to himself and everybody else to teach the peasant the proper use of a spade than to teach him the doctrine of the hatred of England, which is but based on ignorance.

Coláiste na hOllscoile, Gaillimh, agus an Ghaeilge

Dar le glúin réabhlóidithe polaitiúla, b’é iarthar na hÉireann tobar gach a bhí Gaelach agus bhí Conradh na Gaeilge agus na daoine a tháinig roimhe ag iarraidh tús áite a thabhairt an athuair don Ghaeilge sa chultúr náisiúnta.

D’ainneoin shuíomh na hOllscoile in iarthar na tíre, in aice leis an nGaeltacht, bhí léann na Gaeilge ar an imeall i gColáiste na Banríona, Gaillimh, go dtí gur bunaíodh ollúnacht bhuan sa Léann Ceilteach sa bhliain 1897. Rinneadh an ceapachán mar gheall ar bhrú seachtrach agus ní fhéadfadh Coláistí na Banríona neamhaird a thabhairt a thuilleadh ar an éileamh a bhí ar an nGaeilge. Bhunaigh an tAcht um Ollscoileanna na hÉireann i 1908 ollúnachtaí buana le Gaeilge agus ón mbliain 1913 ar aghaidh, rinneadh ábhar éigeantach den Ghaeilge don mháithreánach agus d’iontráil chuig Ollscoil Náisiúnta na hÉireann, a raibh Coláiste na hOllscoile, Gaillimh, ina chomhcholáiste de.

Chonacthas díograis i leith na Gaeilge mar dhualgas tírghrách do náisiúnaithe faoi thús na haoise agus faoin am ar bhris an cogadh amach bhí an Ghaeilge ar an ábhar leis an tríú líon is airde mac léinn sa Choláiste.

Ceapadh Tomás Ó Máille ina chéad Ollamh le Gaeilge sa Choláiste sa bhliain 1909. Rugadh é do theaghlach saibhir i Muintir Eoghain, gar don Mhám i nDúiche Sheoigheach, Conamara, agus bhain sé tairbhe as oideachas iltíreach i mBaile Átha Cliath agus san Eoraip. Rinne sé staidéar ar an tSean-Ghaeilge, an Bhriotáinis agus an Bhreatnais leis an scoláire ceannródaíoch Gearmánach, Kuno Meyer, agus bhain sé amach a dhochtúireacht in Ollscoil Freiburg. Bhí Ó Máille tarraingteach, leathanaigeanta agus thar a bheith meabhrach; ba léiriú é ar ghlúin Chaitliceach, shofaisticiúil, léannta a bhí ar bís chun claontachtaí stát na Breataine a chur ina gceart. Ina iarratas ar Ollúnacht sa bhliain 1909 luaigh sé a mhian chun na buntáistí nádúrtha don Nua-Ghaeilge a bhain le suíomh an Choláiste Ollscoile i réigiún Gaeltachta a fhorbairt ionas go bhféadfaí ionad iontach le haghaidh an léinn in Éirinn, an Léann Ceilteach san áireamh, a dhéanamh den Choláiste. Ba chéim shuntasach a bhí ina cheapachán i dtreo sheasamh na Gaeilge a dhaingniú i léann na hÉireann agus ról tábhachtach a bhunú don Ghaeilge san Ollscoil.

Bhí claontacht in aghaidh na teanga i gcónaí, áfach, agus tar éis Éirí Amach 1916, cháin an nuachtán áitiúil aontachtach, an Galway Express, an ceangal polaitiúil a bhí, dar, leo, idir teagasc na Gaeilge san Ollscoil agus tacaíocht d’fhoréigean polaitiúil:

So much for our College! In the country the whole system of education must be revised and supervised. Let the old language of Ireland have every chance, but let it never again be allowed to cover the spread of sedition. Let us try and realise that it is much more useful to himself and everybody else to teach the peasant the proper use of a spade than to teach him the doctrine of the hatred of England, which is but based on ignorance.