Galway: A University Town / Gaillimh: Baile Ollscoile

War, the most terrible war the world has ever known, has burst upon us with swift and startling suddenness. Armageddon has come.

So began the Connacht Tribune’s editorial following the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914. The war brought great change to Galway society, inadvertently destroying the power of the old Irish Parliamentary Party and contributing to the rise of physical force nationalism. Even before the Home Rule Crisis of 1912, Irish cultural nationalists were increasingly concerned with establishing authentic Gaelic culture at the forefront of national identity in a Gaelic Revival that grew in parallel with the Irish literary revival associated with W.B. Yeats and J.M. Synge. University College Galway reflected this broader cultural ferment. The eruption of the war exposed the division of staff and students into three broad groups: firstly, a sizeable constituency of Catholic Home Rule supporters at ease with loyalty to the crown, secondly, cultural nationalists, who were generally, but not universally, opposed to the war; and thirdly, a significant minority of southern Unionists, often, but not always, Protestants, who enthusiastically supported the British war effort.

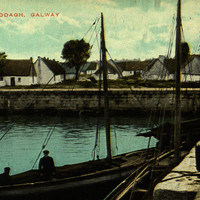

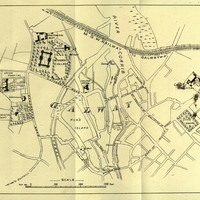

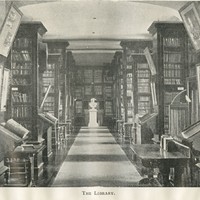

Reports of German atrocities, and in particular, the destruction of academic institutions and libraries, such as in the university town of Louvain where the treasured university library was burned and 248 civilians killed, were viewed as a violation of Germany’s honoured place in European academia and resonated deeply with many Irish academics and scholars. The population of Galway town was approximately 14,000 in 1914 and the town had a long military tradition dating back to the late eighteenth century when the Connaught Rangers were first raised. Thousands of Galway men enlisted on the outbreak of the war out of a mixture of loyalty to John Redmond and economic necessity; over seven hundred Galway men lost their lives fighting with the British Army.

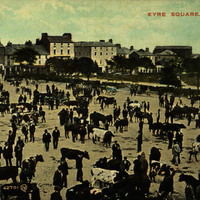

The University was far from immune to the tumult of the period with around 140 students and staff past and current serving with the British military, fifteen of whom lost their lives. Almost seventy students or former students and staff served with the Royal Army Medical Corps, most of whom were attached to the Connaught Rangers. Notwithstanding the scale of the slaughter on the Western Front and during the Gallipoli campaign, support for the war effort remained strong in the town, especially among the families of soldiers and of the Claddagh fishermen called up by the Royal Navy. The visit to Galway of the most senior British official in Ireland, the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Wimborne, provided a much-needed boost to the local supporters of the Irish Parliamentary Party in January 1916. With the main streets bedecked in red, white and blue, National Volunteers (loyal to John Redmond) paraded under royal standards in Eyre Square where a banner proclaimed: ‘One Life, One Navy, One Throne.’ The Connacht Tribune congratulated a town seemingly enthralled by military pomp:

All classes of the community contributed intelligent effort and hearty goodwill toward making it a success, whatever their private leanings. Is there something in the people of Galway which easily disposes them to a deferential recognition of the claims of high authority and glittering prerogative?

What began as an era of profound hope and the promise of Home Rule was to bring division, personal loss and a deep sense of betrayal for those who followed John Redmond’s call to join the war effort; Irish society would never be the same again.

Gaillimh: Baile Ollscoile

War, the most terrible war the world has ever known, has burst upon us with swift and startling suddenness. Armageddon has come.

Ba iad seo na chéad línte in eagarfhocal an Connacht Tribune tar éis bhriseadh amach an Chogaidh Mhóir i mí Lúnasa 1914. Tháinig athrú mór ar shochaí na Gaillimhe de bharr an Chogaidh mar gur scriosadh an chumhacht a bhí ag Páirtí Parlaiminteach na hÉireann roimhe sin agus cuireadh le teacht chun cinn náisiúnachas na láimhe láidre. Fiú roimh an nGéarchéim Rialtas Dúchais sa bhliain 1912, bhí fonn mór ag teacht ar náisiúnaithe cultúrtha na hÉireann fíorchultúr Gaelach a chur chun cinn mar fhéiniúlacht náisiúnta in Athbheochan Gaeilge a tháinig chun cinn le taobh an athbheochan litríochta a bhain le W.B. Yeats agus le J.M. Synge. Thug Coláiste na hOllscoile, Gaillimh léargas ar an gcorraíl chultúrtha níos leithne seo. Le briseadh amach an chogaidh chonacthas trí mhórghrúpa i measc na foirne agus na mac léinn: ar dtús bhí grúpa sách mór de lucht tacaíochta an Rialtas Dúchais–Caitlicigh a bhí sásta a bheith dílis don Choróin; ansin bhí na náisiúnaithe cultúrtha a bhí go ginearálta, ach ní go hiomlán, i gcoinne an chogaidh, agus ar deireadh, bhí mionlach suntasach d’aontachtaithe sa Deisceart, Protastúnaigh den chuid is mó, a thug tacaíocht dhíograiseach do thaobh na Breataine sa chogadh.

Tháinig tuairiscí faoi na hainghníomhartha a rinne na Gearmánaigh, agus go háirithe an scrios a rinneadh i mbaile ollscoile Lováin, áit ar dódh an leabharlann ollscoile mór le rá agus inar maraíodh 248 duine; braitheadh gur shárú ar sheasamh speisialta na Gearmáine i saol acadúil na hEorpa a bhí sna hionsaithe seo agus chuir siad as go mór do lucht acadúil agus lucht léinn na hÉireann. Bhí cónaí ar thart ar 14,000 duine i mbaile na Gaillimhe sa bhliain 1914 agus bhain stair fhada mhíleata leis ag dul siar go dtí deireadh an ochtú céad déag nuair a bunaíodh na Connaught Rangers den chéad uair. Liostáil na mílte fear as Gaillimh san arm nuair a bhris an cogadh amach de bharr meascán de dhílseacht do John Redmond agus riachtanas eacnamaíoch; bhásaigh os cionn seacht gcéad fear as Gaillimh agus iad i mbun troda le hArm na Breataine.

Ní raibh an Ollscoil saor ón réabadh sa tréimhse sin; bhí thart ar 140 duine–iarmhic léinn agus iarchomhaltaí foirne chomh maith le mic léinn agus comhaltaí foirne a bhí ann ag an am–ag troid le hArm na Breataine; bhásaigh cúig dhuine dhéag díobh sin. Bhí beagnach seachtó duine idir iarmhic léinn, iarchomhaltaí foirne agus mic léinn agus comhaltaí foirne a bhí ann ag an am, i gCór Liachta Arm na Breataine, agus bhain an chuid is mó díobh sin leis na Connaught Rangers. D’ainneoin chomh dona is a bhí an sléacht ar an bhFronta Thiar agus le linn fheachtas Gallipoli, d’fhan tacaíocht don chogadh láidir ar an mbaile, go háirithe i measc mhuintir na saighdiúirí agus muintir iascairí ar ghair Cabhlach na Breataine orthu. Thug cuairt an oifigigh ba shinsearaí de chuid na Breataine in Éirinn, an tArd-Leifteanant, an Tiarna Wimborne, ar Ghaillimh an misneach a bhí ag teastáil go géar ó lucht tacaíochta Pháirtí Parlaiminteach na hÉireann i mí Eanáir 1916. Bhí na príomhshráideanna daite dearg, bán agus gorm, mháirseáil na hÓglaigh Náisiúnta (a bhí dílis do John Redmond) faoin mbratach ríoga ar an bhFaiche Mhór, áit a raibh bratach ag fógairt: ‘One Life, One Navy, One Throne.’ Thréaslaigh an Connacht Tribune leis an mbaile a bhí faoi dhraíocht ag mustar míleata:

All classes of the community contributed intelligent effort and hearty goodwill toward making it a success, whatever their private leanings. Is there something in the people of Galway which easily disposes them to a deferential recognition of the claims of high authority and glittering prerogative?

Thosaigh an tréimhse lán le dóchas agus le gealltanas an Rialtas Dúchais ach chríochnódh sé le deighilt, caillteanas pearsanta agus bhraith siad siúd a lean glao John Redmond a bheith páirteach sa chogadh go raibh siad tréigthe; ní bheadh sochaí na hÉireann mar a chéile go deo arís.